The concept of private property was introduced during the British rule through the Zamindari, Ryotwari and the Mahalwari systems of land ownership which led to highly unequal land distribution; while the Indian Forest Act (1927) converted all forest land into government-ownership, doing away with the traditional community ownership by the forest-dwellers. The Indian Constitution, following the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, upheld the right “to acquire, hold, and dispose of property” as a fundamental right. However, post the 44th Amendment, right to property became a legal right and ceased to be a fundamental right.

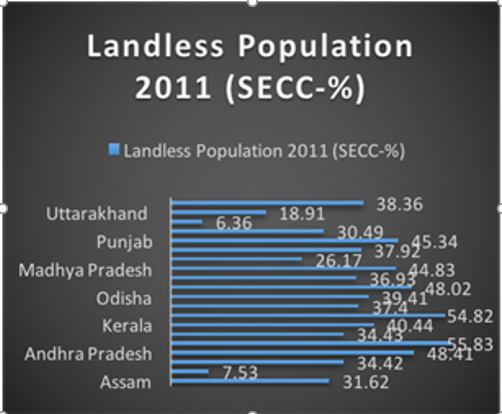

Land distribution in India is highly unequal with only seven percent of Indian controlling more than 47 percent of land while the rest 93 percent have to live with 53 percent of land (NSSO, 2013). Number of landless population in India has increased, according to the Socio-Economic Caste Census 2011. Around 38.63 percent population in India are landless and majority of them belong to the marginalised community- Dalits, tribal and female headed households. Very few and handful of women have land ownership in India despite their significant contribution to agriculture and natural resource management. Unavailability of gender disaggregated data makes the monitoring of women land ownership quite difficult.

Land (re)distribution or land reform, has been a significant challenge in India. The land reform experience in India has met with serious challenges due to limited will, weak laws and weaker enforcements for the benefit of smallholder, marginal, tribal, rural groups. While 15-21 million Acre of ceiling surplus land is technically available, the actual performance of vesting and redistribution is far from satisfactory. So far, only 5.5 million households have received ‘surplus land’ of 1.9 million hectares.

Limited political will on addressing the rise of absolute landless households – Amidst the general failure of land reform to distribute land to the poor in general, the rise of absolute landless households across the nation is alarming.

“More recent data is available from the 2013 National Sample Survey Office – NSSO survey, that surveyed only rural areas and showed that the proportion of landless households decreased to 7.4%, or 11 million households and 57.7 million people1”. It is still an impressive number.

However, none of the states have done anything particular, to alter any part of their laws or policy. The land ceiling and redistribution legislations continued to define landless in the same way.

Lack of legal protection on government-led allocation programs for absolute landless – Meanwhile, since around 2005-2006, several state governments started land purchase program and special land allocation program for the absolutely landless. However, none of these programs has any legal protection. Later in 2009, the central government came up with a land purchase program for absolutely homestead-less households to provide them with housing under Indira Awas Yojana[1]. This too was not backed up by legislation. Several state governments have thereafter taken up homestead land purchase in order to reach out to more absolutely landless people that are not backed up by any legislation. These programmes had the potential to invoke and resurrect the Land Ceiling Act[2] and the legal provisions therein but failed to do so for lack of political will.

Accordingly, a large part of the land technically ‘vested’ and/or ‘redistributed’ to the poor, are still not possessed by the poor with land titles on their names. They are either with their (erstwhile) landlords or as barren lands. Majority of the Bhoodan Lands[3] are in possession of powerful local individuals. A critical challenge is to make the state work to recover these and hand over possession to the landless, including absolutely landless.

Land Acquisition for investments is a widely debated topic today in India. For the last five years, the legal framework of land acquisition has been debated in this country from multiple perspectives, and in 2013 the land acquisition bill was passed in Parliament. There was increased recognition that the existing law of 1894 as amended in 1950 was grossly inadequate to address the new situation where development has to honor human rights, justice, and sustainability issues.

[1] A scheme of the government for land to the landless for constructing house

[2] This is one of the most powerful land reform ever introduced which ensures the ceiling of surplus land in the possession of zamindars (feudal land lords) and its redistribution

[3] Immediately after independence, there was a movement launched by renowned social reformist to donate the surplus lands. The movement marked huge success.

LFI contribution to the component in last two years:

- With a constant push from Ekta Parishad, the ‘Madhya Pradesh Housing and Homestead Act, 2017’ has been enacted.

- Keeping the land reform agenda alive in the national agenda- the formulation of the "draft land reform policy" during the land government and still lobbying with the state and central governments for its implementation

- In Uttarakhand, LFI member has undertaken legal procedures on land cases and land laws. The outcomes of these procedures have the potential to policy changes in other states and national level

- To aware LFIs building of the CSOs, social workers and communities on various acts and laws such as FPIC, provisions of LARR, Land Ceiling Act, etc with lawyers and legal activists working on land issues.

- Aware LFIs of land rights amongst marginalised communities, Self Help Groups for building the grassroots movements

- Documentation of land struggles- LFI India have few good documents besides the individual organisations' research and documentation work on land struggle that might be useful